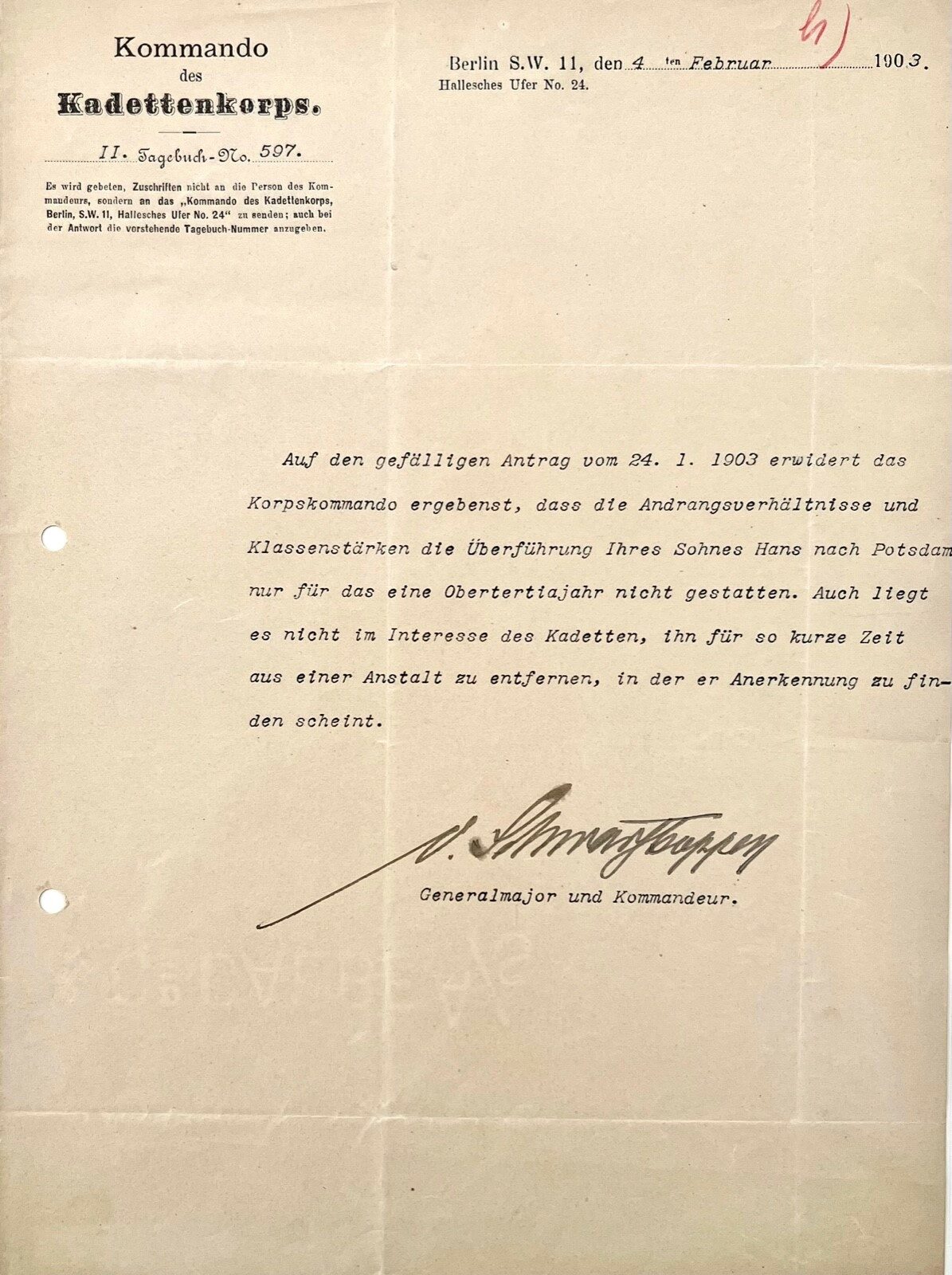

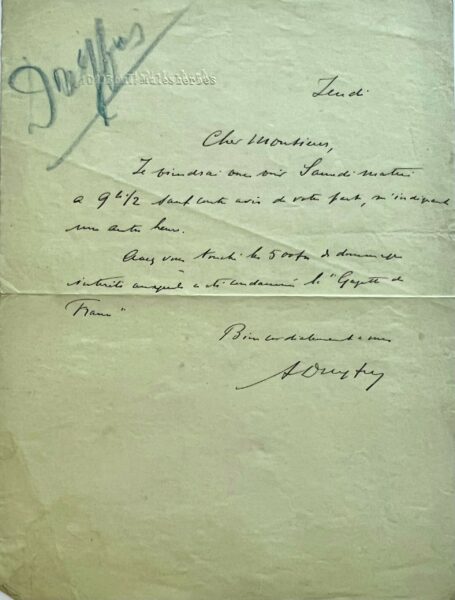

On September 26, 1894, several weeks after French Major Ferdinand Esterhazy met with Colonel Max von Schwartzkoppen, Germany’s military attaché at its embassy in Paris, who had engaged Esterhazy as a spy, Mme. Bastian, a cleaning woman employed by French Counterintelligence, removed the contents of Schwartzkoppen’s wastepaper basket and delivered the scraps to her supervisor, Major Henry. The trash contained remnants of a memorandum, or bordereau, which listed army documents that could be made available to Schwartzkoppen, leading Henry to believe that a spy, likely a French artillery officer, was working at French General Staff headquarters. On October 6, Major Armand Du Paty de Clam was shown the bordereau and asked to compare the handwriting to a sample from Captain Alfred Dreyfus. Du Paty concluded that they were written in the same hand. Although Dreyfus had thus far enjoyed a reasonably successful military career, he remained unpopular with many comrades who, influenced by nascent French anti-Semitism, associated Judaism with decadence, moral corruption, rabid opportunism, and betrayal. He was arrested and imprisoned on October 15, 1894.

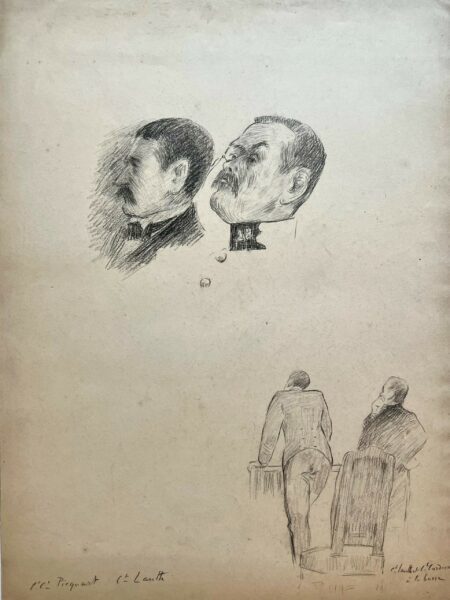

Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen

On February 21, 1895, following his 1894 trial and conviction for treason, Dreyfus was sent to Devil’s Island in French Guyana. While his family tried to clear his name, Dreyfus languished for years in solitary confinement, as a vast network of anti-Semitic French journals regularly circulated rumors and lies about him. Esterhazy and Major Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had forged much of the supporting evidence used against Dreyfus, conspired to cover up their involvement by forging additional evidence.

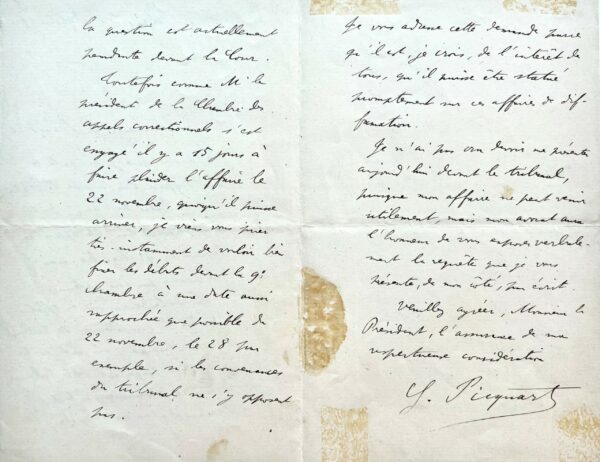

The truth finally emerged in the summer of 1898 after Henry confessed and then killed himself in a military prison and Esterhazy fled to England. Considering these events, the court annulled the 1894 judgment against Dreyfus and granted him a second military trial in 1899 where the court, despite overwhelming evidence that pointed to a broad conspiracy to frame him, by a majority of five to two, again found Dreyfus guilty of treason, but under “extenuating circumstances.” Sentenced to ten years detention, French president Émile Loubet offered Dreyfus a pardon, which he initially refused as it would compel him to withdraw his petition for a legal revision and accept responsibility for a crime, he steadfastly maintained he never committed. Dreyfus ultimately acquiesced, provided he could continue to try and prove his innocence. Despite efforts by the anti-Dreyfusards and their advocates in the press, the Court of Cassation finally cleared Dreyfus’ name in 1906. The Dreyfus Affair’s significance is so far-reaching that the human rights movement, the beginnings of Zionism (Herzl was the Paris correspondent for Vienna’s Neue Freie Presse at the time), and the French separation of church and state can all claim to have originated during this dark chapter in French history.

Schwartzkoppen’s espionage activities while in Paris lasted from 1891-1897, where he shared intelligence with his colleague, Italy’s military attaché in Paris, Alessandro Panizzardi. Though he and Panizzardi knew Dreyfus was innocent, Schwartzkoppen did not disclose any information other than continually denying ever knowing Dreyfus. The posthumous publication of his diary confirmed Dreyfus’ innocence. Our letter was written following Schwartzkoppen’s return to military duties in Germany and prior to his 1908 retirement with the rank of general. At the outbreak of World War I, he reenlisted and served as an infantry general, dying from pneumonia in 1917.

Signed as Major General and Commander. Two file holes in the left margin, otherwise fine. Scarce.