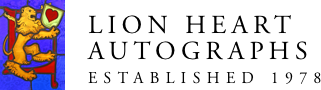

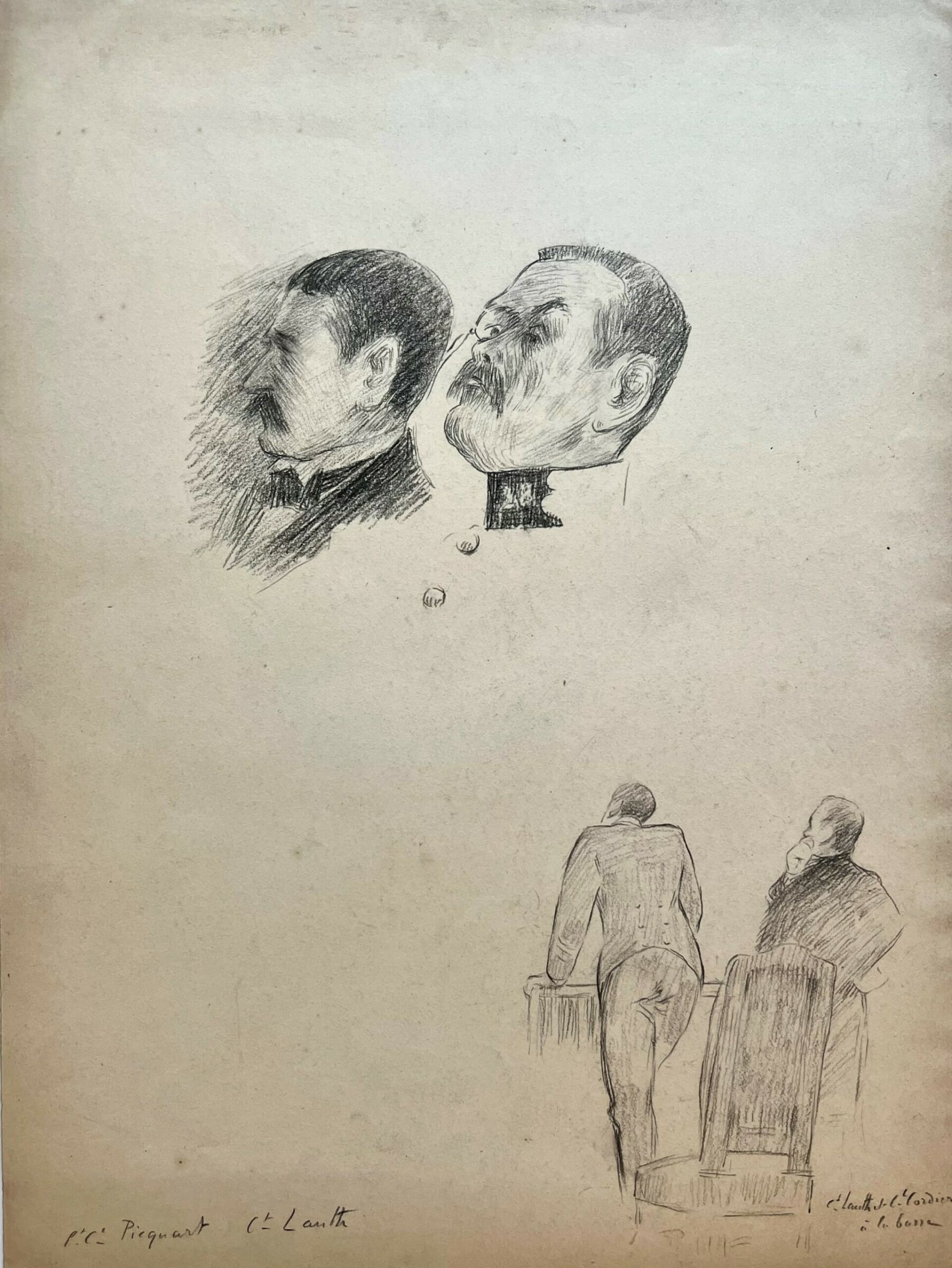

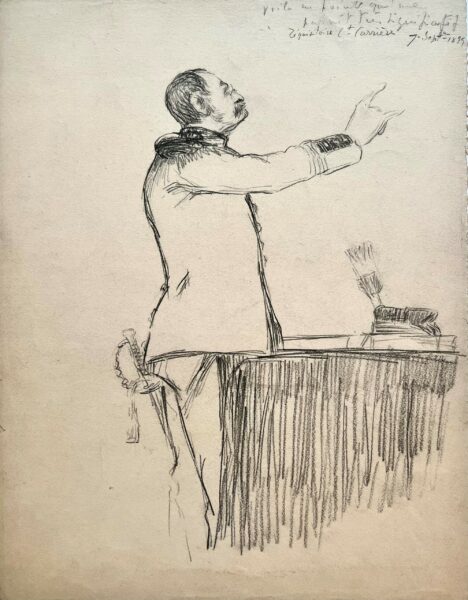

[DREYFUS, AFFAIR.] BOUCHOR, JOSEPH-FÉLIX. (1853-1937). French portrait artist. Drawing. 1p. Large 4to. (9 ½” x 12 ½”). [Rennes, August 29, 1899]. Bouchor’s eyewitness, double portrait courtroom pencil sketch of French army Lieutenant-Colonel Georges-Marie Picquart (1854-1914), Dreyfus’ instructor at the War College and chief of military intelligence who, in 1896, after reviewing a pneumatic tube telegram (the petit bleu) sent from the German Embassy’s military attaché, Schwartzkoppen, to Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, the agent whose espionage activities had been pinned on Dreyfus, opened an investigation into Esterhazy. Next to Picquart is a sketch of a haughty looking officer, Jules Maximilien Lauth (1858-1943), an antisemitic member of the army’s General Staff and translator of German documents for the Statistical Section who forged evidence against Dreyfus and who, after 1895, was Picquart’s subaltern. In the bottom right corner is a sketch of two individuals identified as Lauth and Statistical Section Commandant Albert Cordier “at the bar,” during the trial at Rennes.

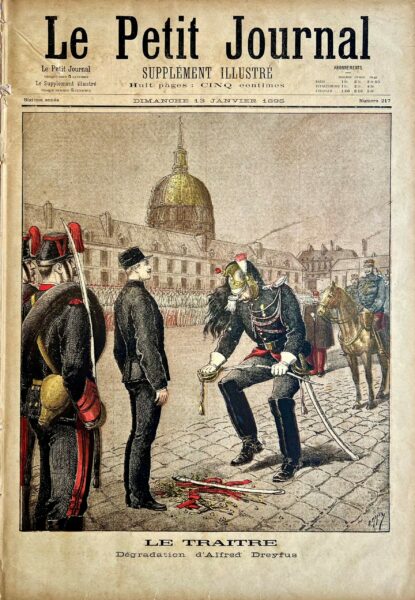

Alfred Dreyfus’ 1894 conviction for treason and his subsequent exile and imprisonment on the French Guiana penal colony Devil’s Island hinged on an intercepted memo, or bordereau, which revealed French military secrets that had been sent anonymously to the German embassy’s military attaché, Captain Schwartzkoppen, in Paris. The memo’s actual author was French Major Marie-Charles-Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, a spy in German employ. Additional evidence, intended to implicate Dreyfus, was secretly forged and submitted by French Army officers to the military judges presiding over the proceedings.

Picquart took over the military counter-intelligence section at the French War Ministry in 1895 and his assistant, Lauth, brought him the petit bleu, fragments of a pneumatic tube telegram which implicated Esterhazy and exonerated Dreyfus. Picquart initiated a secret investigation into Esterhazy, while being spied on and deceived by members of his own staff, Captain Lauth and Lieutenant Colonel Hubert-Joseph Henry. Engaged in a broad cover-up, the army first punished Picquart by re-assigning him to active duty in Tunisia. Then, upon Esterhazy’s acquittal on January 11, 1898, Picquart was imprisoned the day Emile Zola’s letter J’Accuse…! was published. Picquart testified at Zola’s libel trial and became one of Dreyfus’ most outspoken supporters. On February 1, 1898, Picquart was “discharged for gross misconduct in the service,” effective February 26th, three days after Zola was found guilty. Picquart was then falsely accused of forging the petit bleu, which led to his second imprisonment on July 13th, five days before Zola’s second conviction. Petitions for his release, signed by thousands of people, were circulated in Le Siècle and L’Aurore before he was freed in June 1899. He later became Clemenceau’s Minister of War.

The truth of Dreyfus’ innocence finally emerged in the summer of 1898 after Henry confessed to his forgeries, committed suicide, and Esterhazy fled to England. General Boisdeffre, the army’s Chief of the General Staff who had been convinced of Dreyfus’ guilt from the beginning, resigned after Henry’s confession. Considering these events, the court annulled the 1894 judgment against Dreyfus and granted him a second military trial in Rennes. Dreyfus, frail and in poor health, sailed from his island exile on June 9, 1899, to appear at the Rennes trial on August 7th.

Journalists and artists from around the world swarmed Rennes to observe the trial that would be “a culminating point of l’affaire. It was the last opportunity for the military system of justice to redeem itself… The first military tribunal [in 1894] had been able to insist that no hearings be conducted publicly. At Rennes, the second military tribunal held all hearings publicly, except for one, and the fact that the court insisted on holding any at all behind closed doors both exacerbated criticism of the proceedings and was hotly contested by the defense, for this time the eyes of the country and of the world were fixed on Rennes. The world press was ready to convict France if France convicted Dreyfus. And France itself, author of the Rights of Man and Citizens, country of the philosophes, and of the Enlightenment, was only too painfully aware of this,” (“The Military Trial at Rennes: Text and Subtext of the Dreyfus Affair,” Touro Law Review, Curran). The trial was covered in detail by newspapers and magazines worldwide and was even dramatized in Georges Méliès series of short silent films, produced concurrently with the trial becoming the first ever film serial! (Nine of the eleven films can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y3Re6Y1G8_U).

“By the time the Rennes trial took place, proof of his innocence abounded,” (The Affair: The Case of Alfred Dreyfus, Bredin). He was defended at court by Edgar Demange, who had been engaged by his family in 1894, and by prominent criminal attorney Ferdinand Labori, who had defended Emile Zola after his famous publication of J’Accuse…! One week into the trial, on August 14, Labori was shot in the back by a would-be assassin on his way to the courtroom. Though badly wounded, he returned to court on August 22. During the trial “Dreyfus spoke at length, and always confidently and with impressive specificity and precision, reconstituting events, showing how and why his accusers could not be telling the truth… On numerous occasions throughout the trial, he broke out in protest against the injustice and inaccuracy of testimony and, as he put it, its calumnious nature,” (op. cit., Curran).

Picquart, Lauth and Cordier were among the numerous witnesses called upon to give evidence during the trial. On August 29, Cordier testified, “that his belief in the guilt of Dreyfus has reversed since 1894 because of the campaign against Picquart, led mainly by Henry…Cordier also discloses that from 1895 Henry, Lauth and Gribelin plotted against their superior Picquart. Cordier’s evidence provokes vehement protest, especially from Lauth…” (The Dreyfus Affair, A Chronological History, Whyte, pp. 269-270. For additional details about Cordier’s testimony, depicted in our sketch from the trial, see: “Cordier Acquits Dreyfus,” New York Times, August 30, 1899, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1899/08/30/100449919.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0.) On September 9, the judges, by a majority of five to two, found Dreyfus guilty of treason under the absurd concept “extenuating circumstances,” and sentenced him to ten years detention. Ten days later President Émile Loubet issued Dreyfus a pardon. Dreyfus, initially opposed to accepting any pardon as it would have compelled him to withdraw his petition for a legal revision and acknowledge responsibility for a crime he steadfastly maintained he never committed, finally acquiesced, providing he could still try to clear his name.

Despite the ongoing vitriolic attacks in the press and public displays by anti-Dreyfus elements, the Court of Cassation finally declared Dreyfus innocent 1906. The Dreyfus Affair’s significance is so far-reaching that the human rights movement, the origins of modern-day Zionism (Theodor Herzl was in Paris covering Dreyfus’ first trial for his Viennese newspaper), and the French separation of church and state can all claim to have been born during this dark chapter in French history.

Educated at the Beaux-Arts and an exhibitor at the Salon des Artistes Francis, Bouchor became known for his portraits of General John Pershing and French President Georges Clemenceau (a supporter of Dreyfus and publisher of Zola’s “J’Accuse…!”) as well as his illustrations of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I and Orientalist paintings inspired by his travels in North Africa.

Provenance: Isabelle Lazar (nee Grumbacher), wife of Jewish journalist Bernard Lazare, anarchist, literary critic and one of Dreyfus’ earliest and most vocal defenders who covered the Rennes trial for The Chicago Record and The North American Review.

In very fine condition.