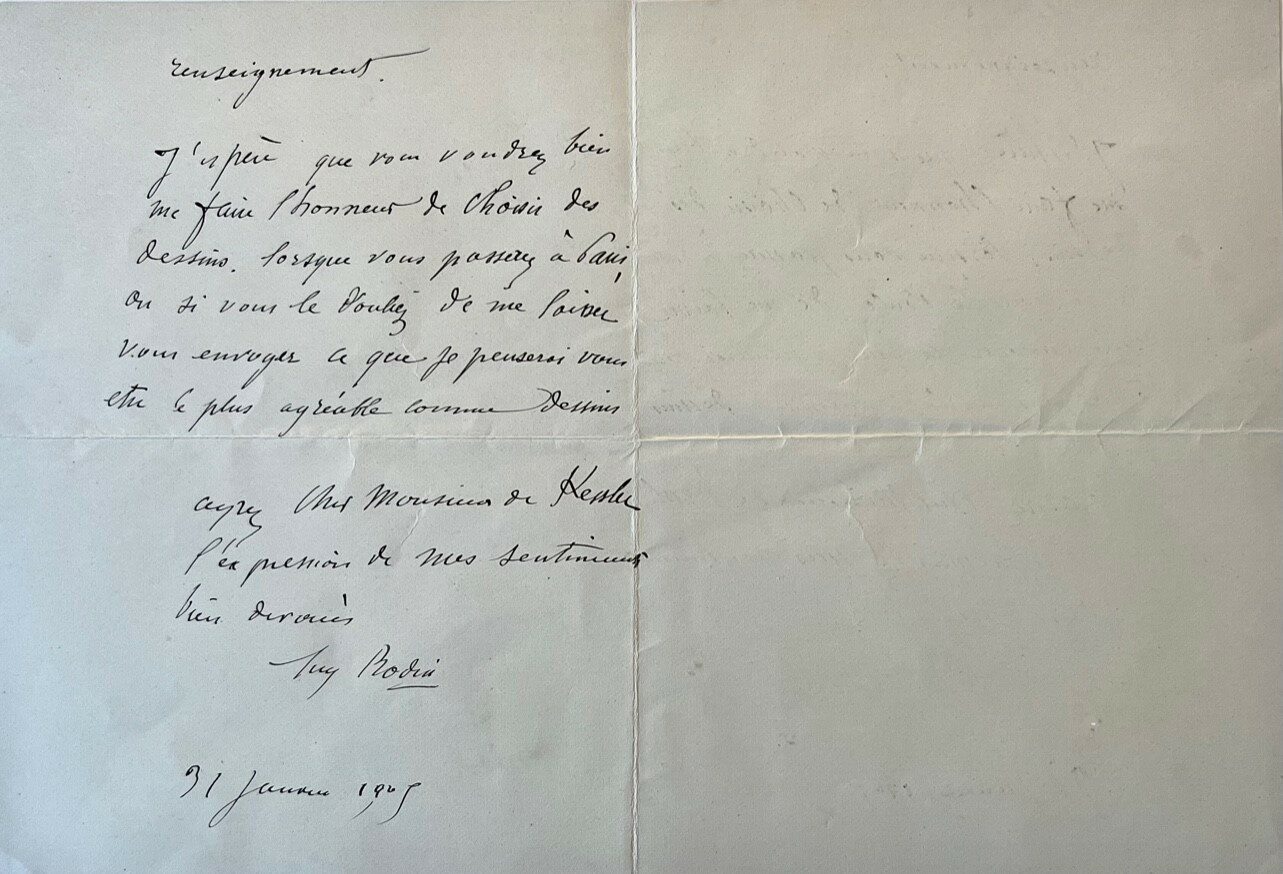

I hope you will do me the honor of choosing drawings when you come to Paris or, if you wish, to let me send you what I think will be the most pleasant drawings for you.

Accept, dear Mr. de Kessler, the expression of my very devoted feelings…”

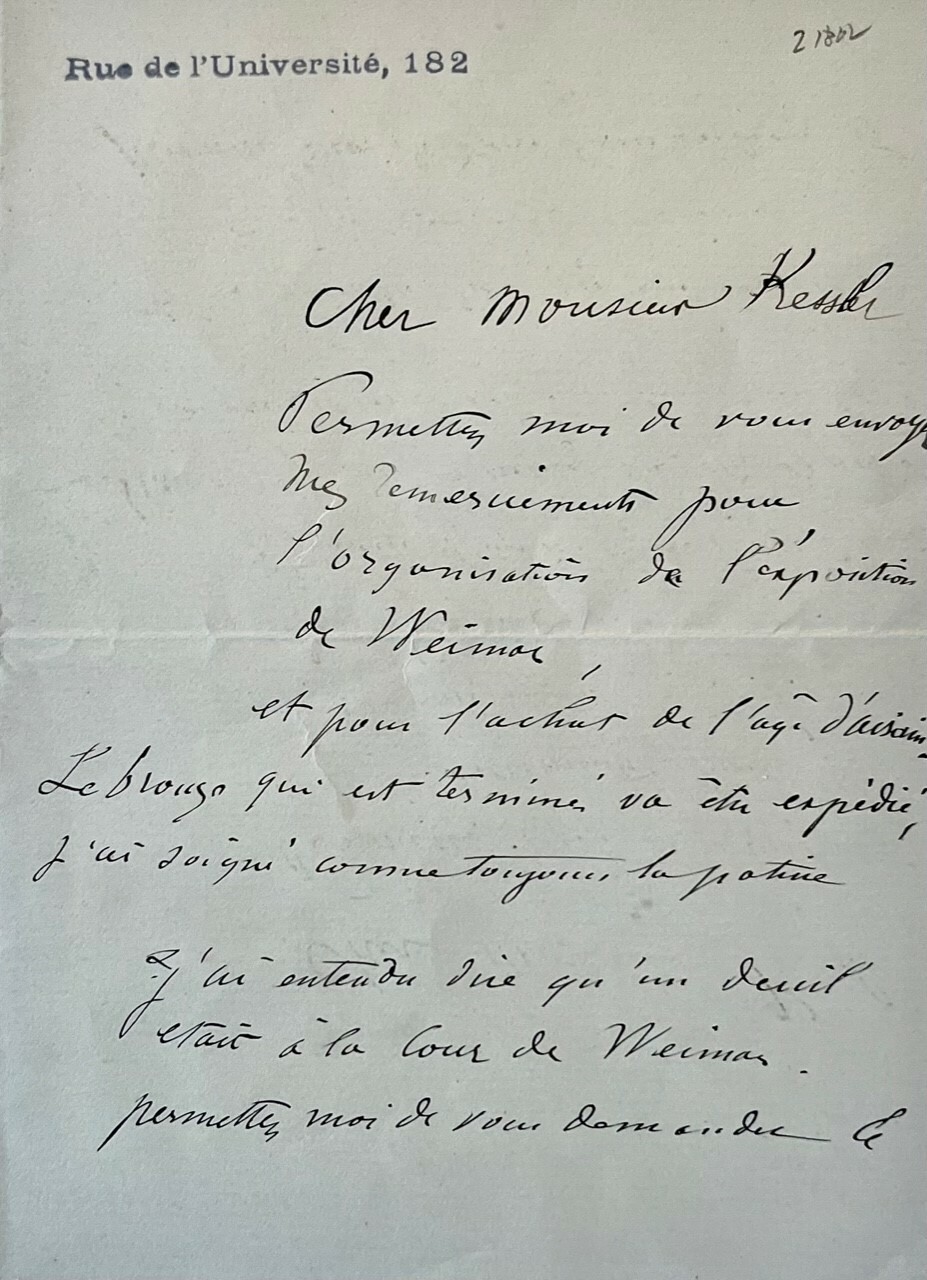

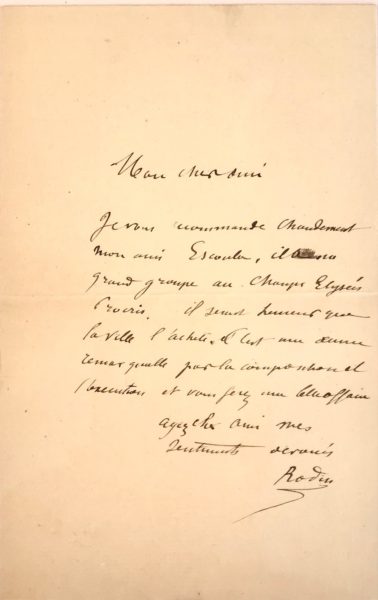

Rodin’s L’Âge d’Airain

Rodin’s characteristic rough-hewn style and virtuoso technique made him the leading sculptor of his time, placing him at the vanguard of modern art. Perhaps Rodin’s best-known work is the monumental and elaborate The Gates of Hell, a pair of bronze doors commissioned in 1880 for the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, and The Thinker, which drew inspiration from this immense and complex project. During the 1870s, Rodin traveled throughout Italy where he was influenced by the work of Michelangelo and began to sculpt male nudes including Adam, Saint John the Baptist and The Age of Bronze (L’Age d’airain), Rodin’s first major work, was inspired by Michelangelo’s Dying Slave and based on a 22-year-old Belgian soldier named, Auguste Neyt. The realistic sculpture created a controversy in 1877 when Rodin exhibited it at the Paris Salon and was accused of casting a mold over a living person. Rodin sold casts of the statue to various institutions including Weimar’s Schlossmuseum.

In October 1902, Kessler, the Paris-born son of a German banker and Anglo-Irish aristocrat, was appointed director of the Grand Ducal Museum of Arts and Crafts at the urging of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the sister of the German philosopher of whom Kessler was an early adherent. Viewing Germany as culturally backward in comparison to France and England, where he had been educated, Kessler endeavored “to turn the somnolent Museumstadt [Weimar] into a center of aesthetic modernism in Wilhelmian Germany,” (“The Rise and Fall of the ‘Third Weimar’: Harry Graf Kessler and the Aesthetic State in Wilhelmian Germany, 1902-1906,” Central European History, Easton). Despite his admiration of William Morris’ Arts and Crafts aesthetic, “the interest in the völkisch arts and crafts to the peasants of small towns left him cold… He took seriously Nietzsche’s strictures on developing a ‘good Europeanism’ as the basis for cultural rebirth,” (ibid.). Publicly defending what he felt was the state’s obligation to fund art and culture, he put forth Weimar as “the seedbed for a new culture, suitable for the modern age and for a great nation,” (ibid.).

In the summer of 1904, Kessler exhibited 16 Rodin statues along with photographs of his work and 33 “movement and silhouette studies,” followed, in 1906, by a second Rodin exhibition of drawings and watercolors, which Rodin then donated to the museum, likely the artworks referenced in our letter, (ibid.). The alleged pornographic nature of Rodin’s drawings, for which Kessler had erroneously thanked the Grand Duke of Saxe-Thuringian for donating, created a controversy that was covered in the national press with Kessler’s enemies at court eventually prompting his resignation in July 1906, “just two days before Edvard Munch had completed the famous full-length portrait of Kessler now in the National Gallery in Berlin, perhaps the greatest picture of a connoisseur ever painted,” (ibid.). Interestingly, Kessler later helped develop, with his friend Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the plot for Richard Strauss’ opera Der Rosenkavalier.

Rodin’s letter likely refers to the recent death of Princess Caroline Reuss of Greiz, the first wife of William Ernest, the reigning Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. Persuaded to enter into what was an unhappy marriage with a member of one of the most stifling royal courts in Europe, Princess Caroline caused a scandal when she fled to Switzerland. She was convinced to return to court only to lapse into ill health and melancholia, dying mysteriously – possibly of suicide – on January 17, 1905, after only 18 months of marriage.

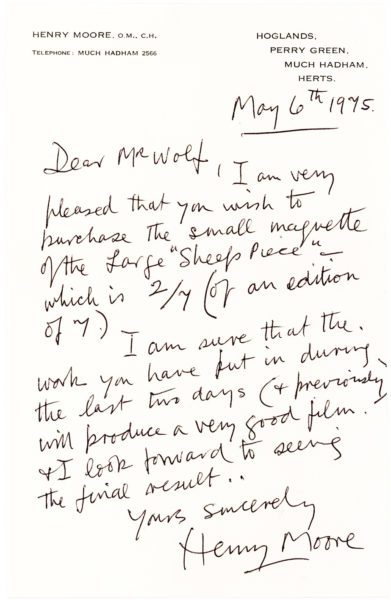

Written on the first two pages of a folded sheet and in excellent condition.