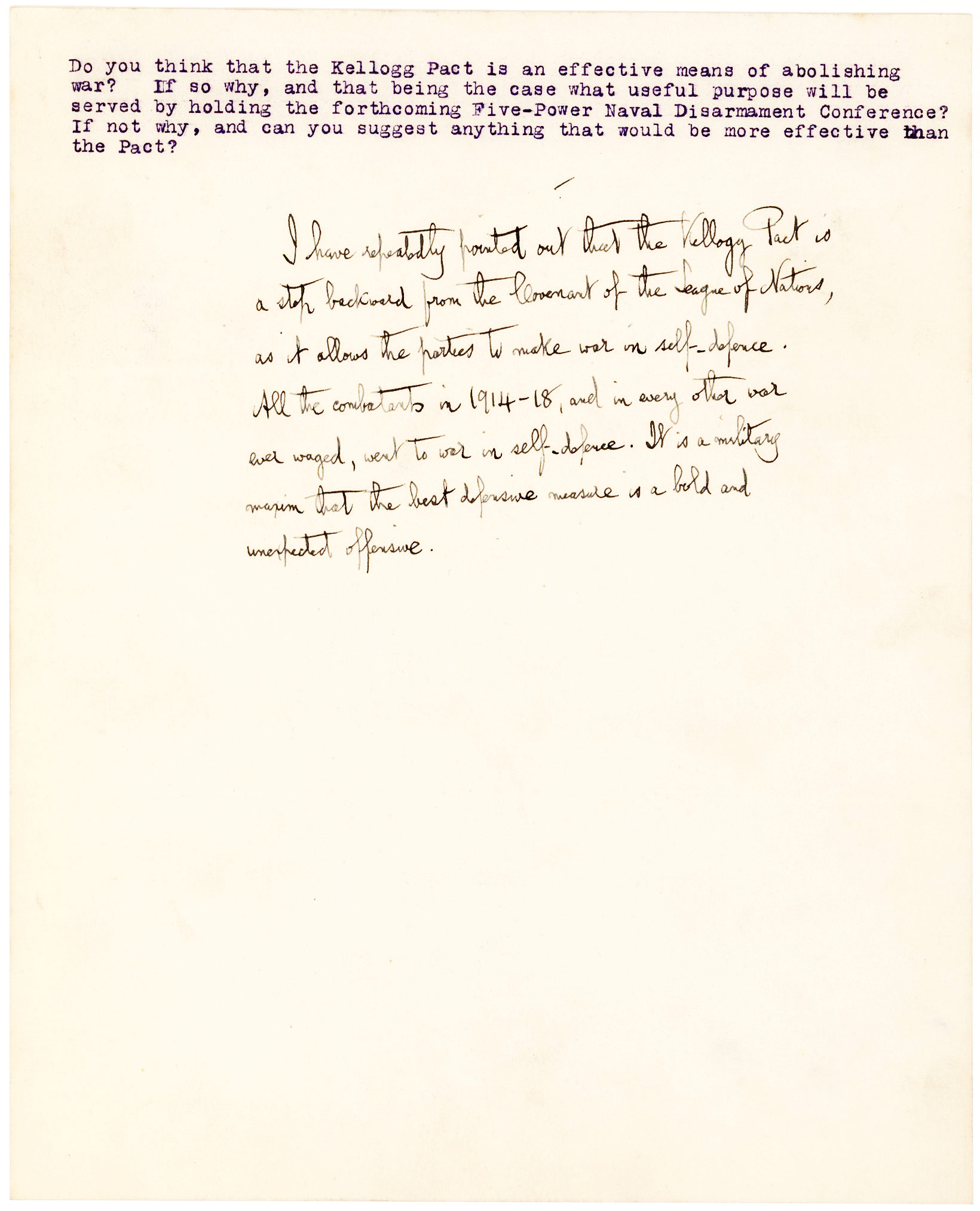

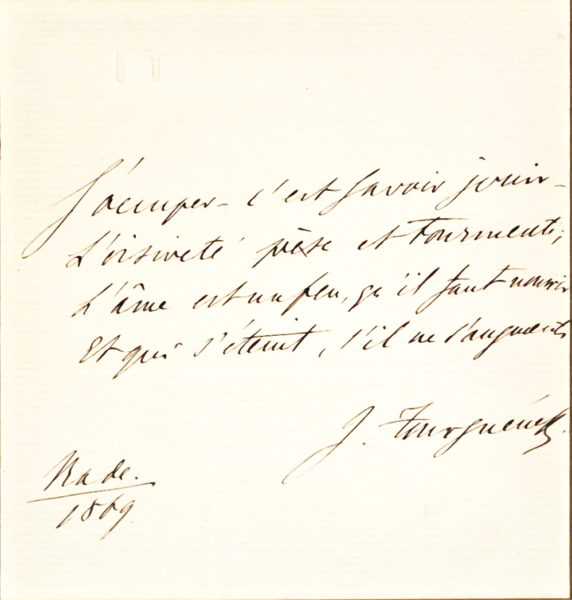

SHAW, GEORGE BERNARD. (1856-1950). Nobel Prize-winning Irish playwright and critic known for his many plays including The Devil’s Disciple and Pygmalion. AMs. Unsigned. ½p. 4to. N.p., N.d. [London, December 4, 1929]. (To journalist HENRY LOSTI RUSSELL, 1896-1968.) Shaw’s handwritten response to a typed question inquiring, “Do you think the Kellogg Pact is an effective means of abolishing war? If so why, and that being the case what useful purpose will be served by holding the forthcoming Five-Power Naval Disarmament Conference? If not why, and can you suggest anything that would be more effective than the Pact?”

“I have repeatedly pointed out that the Kellogg Pact is a step backward… as it allows the parties to make war in self-defence… It is a military maxim that the best defense is a bold and unexpected offensive”

“I have repeatedly pointed out that the Kellogg Pact is a step backward from the Covenant of the League of Nations, as it allows the parties to make war in self-defence. All the combatants in 1914-1918, and in every other war ever waged, went to war in self-defence. It is a military maxim that the best defense is a bold and unexpected offensive.”

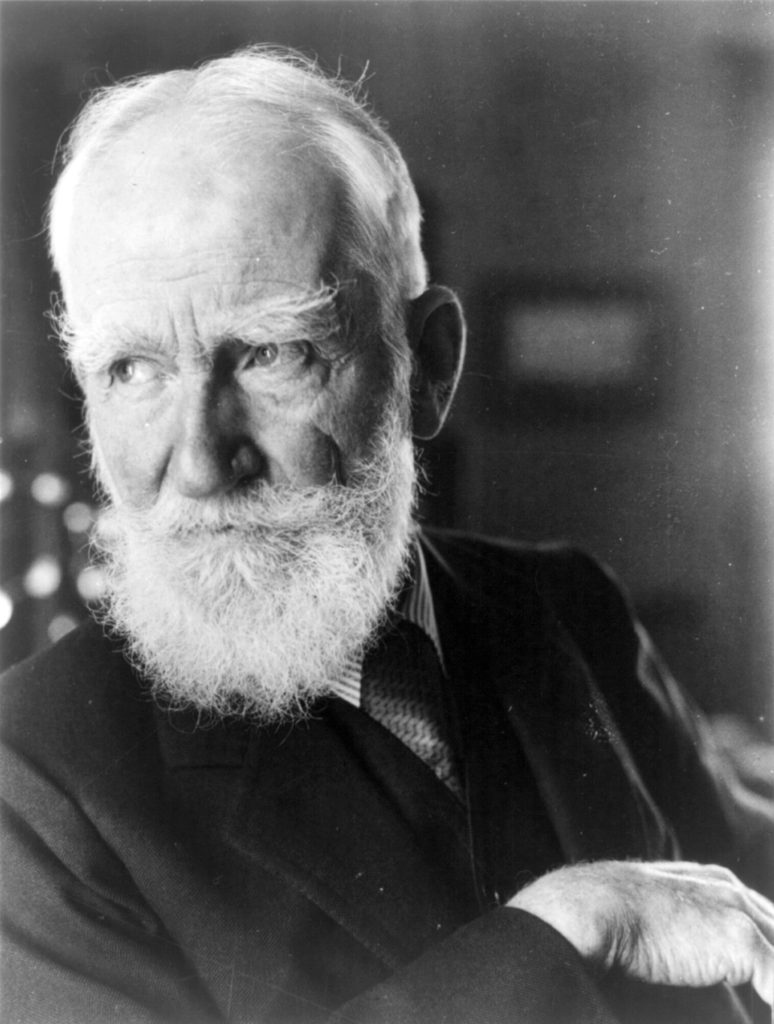

George Bernard Shaw

Shaw began his writing career on April 21, 1894, when his play Arms and the Man, which explores the futility of war, opened to great acclaim in London. His foremost international success, it represented “the true beginning of [his] recognition as a popular dramatist,” (Encyclopedia Britannica). Likened by some to Shakespeare, Shaw combined satire, comedy and social criticism in his more than 50 plays. His famous stage works include Saint Joan (for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1925), Man and Superman and Pygmalion, the inspiration for the popular musical My Fair Lady.

The horrors of World War I led Shaw to abandon his pursuit of socially critical drama, and to criticize the period instead. During the war Shaw published a controversial pamphlet, Common Sense about the War, suggesting that both Great Britain and the Allies were as responsible as the Germans for committing atrocities, and argued for negotiations and peace. He also gave numerous anti-war speeches that provoked much criticism at home. In 1928, Shaw authored The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism and Fascism, and by the 1930s he had self-identified as a communist. Shaw’s strong opinions on the Treaty of Versailles, signed in Paris after war’s armistice, likely led to the frequent solicitation of his opinion.

In 1922, the United States, Japan, France, and Italy signed the Five Powers Treaty at the Washington Conference, which limited future naval growth. President Calvin Coolidge invited the signatories to revisit the subject in 1927; however, France and Italy declined, leaving Japan, Great Britain and the United States to meet at the Geneva Naval Conference and discuss naval limitations. The parties failed to reach an agreement, which led to a third meeting, the London Naval Conference of 1930, at which time Great Britain, the United States, Japan, France, and Italy attempted to discuss disarmament and revise the terms of the Five Power Treaty of 1922.

Shaw penned our comment more than seven months after the effective date of the Kellogg-Briand Pact which called for peaceful settlement of future disputes between its original signatories, France, the United States and Germany, and later the United Kingdom, Soviet Union and other countries who agreed to adhere to its principles. He also references the Covenant of the League of Nations, the organization’s charter drafted by Woodrow Wilson in 1919 and ratified as part of the Treaty of Versailles.

In excellent condition.