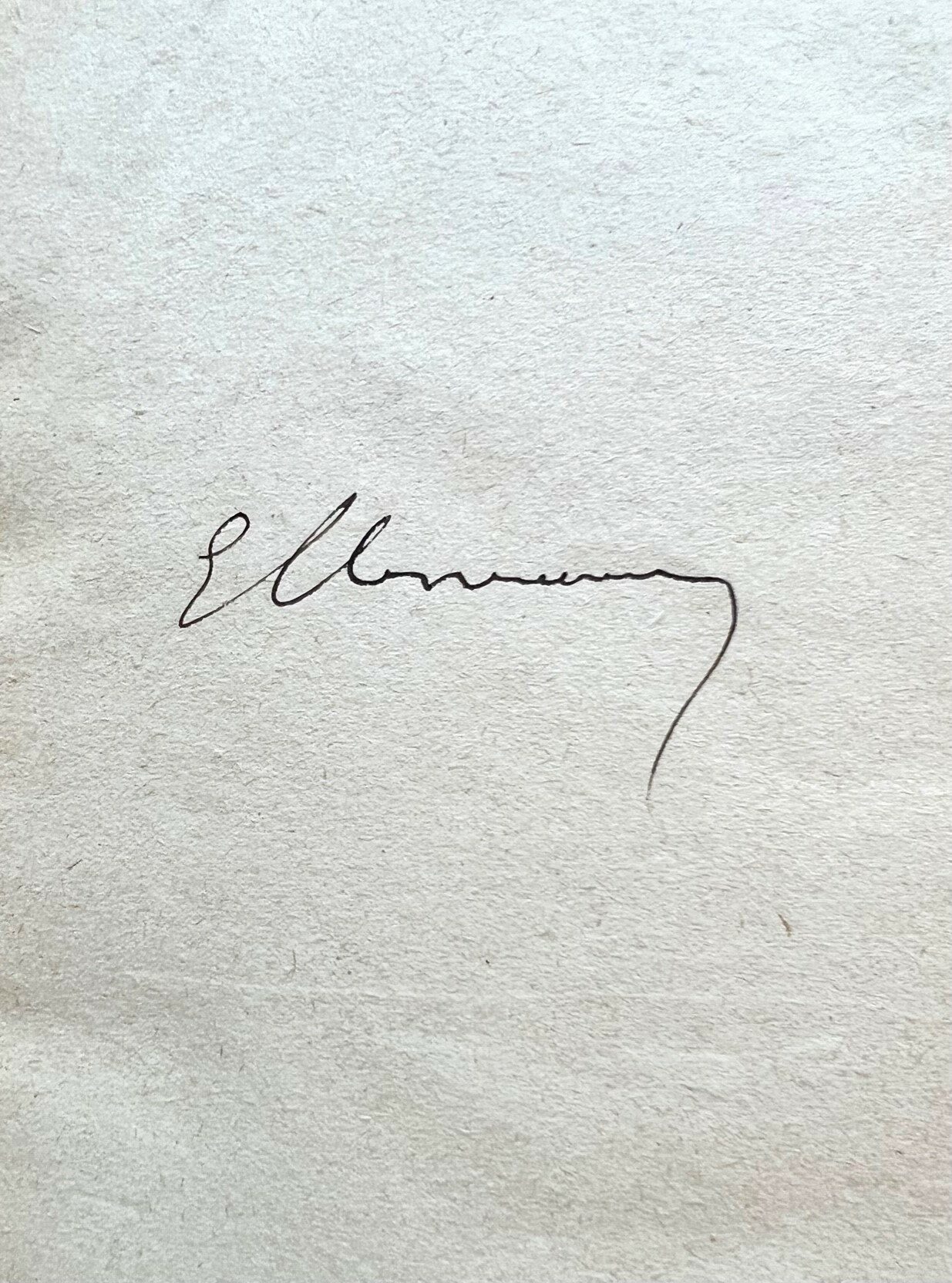

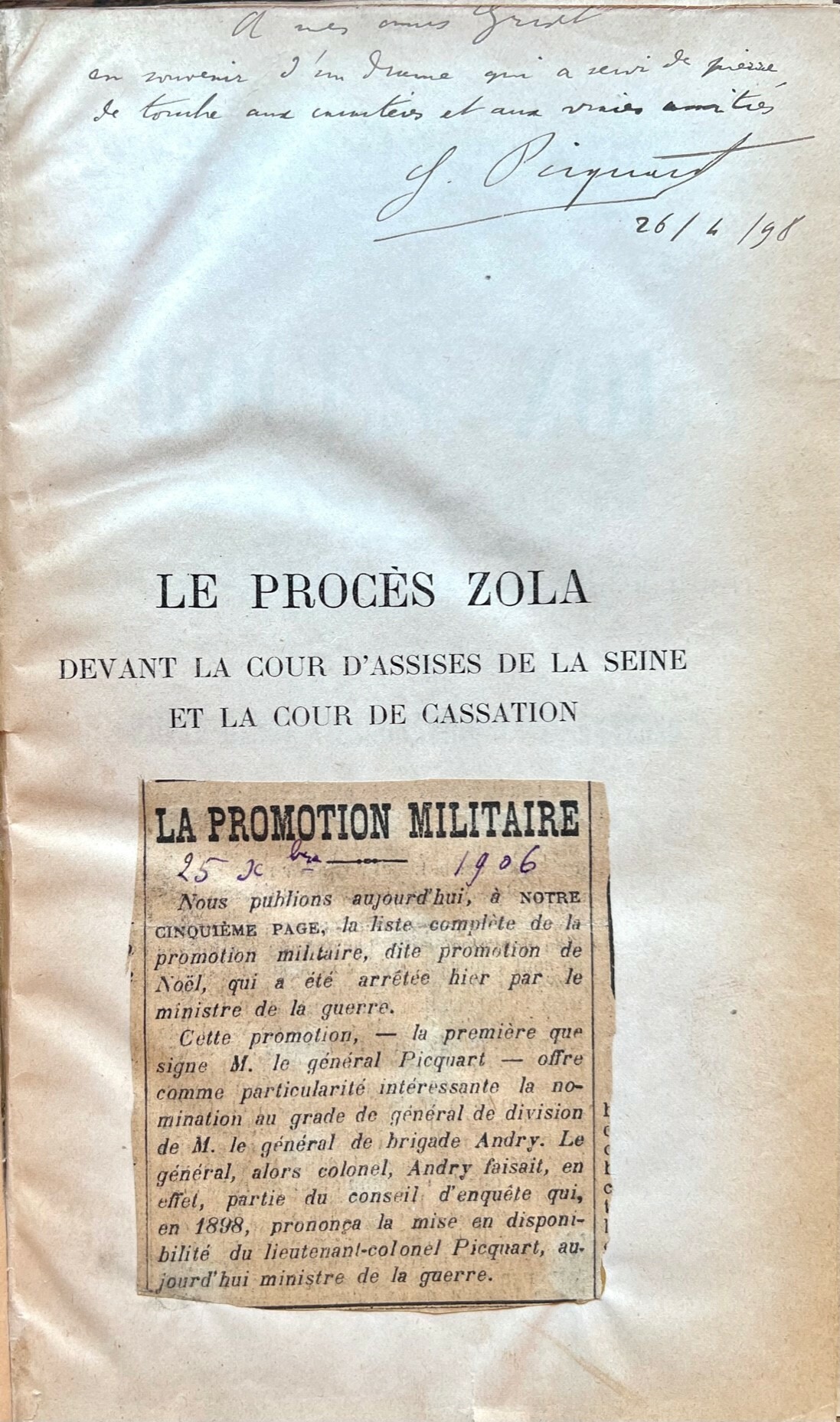

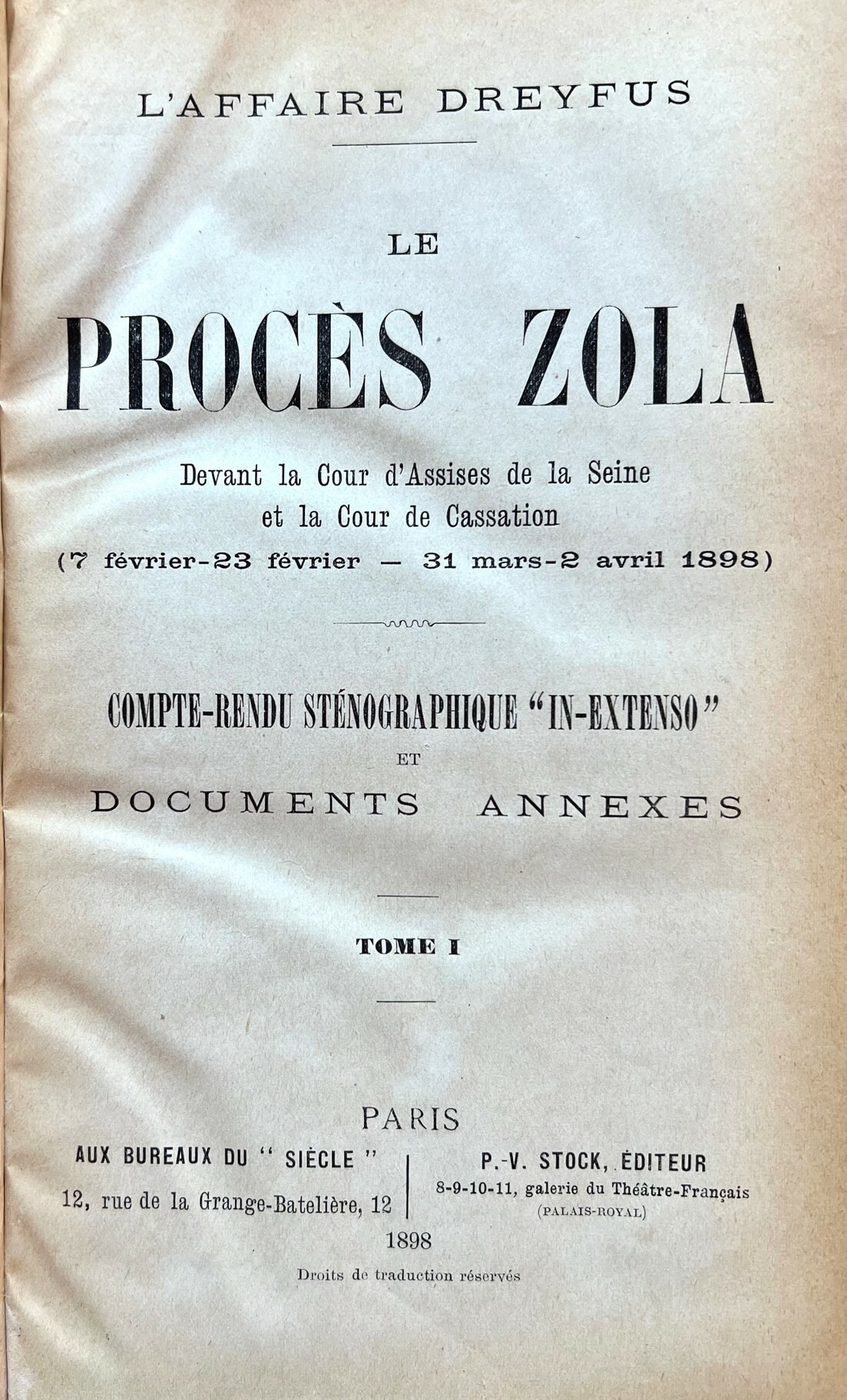

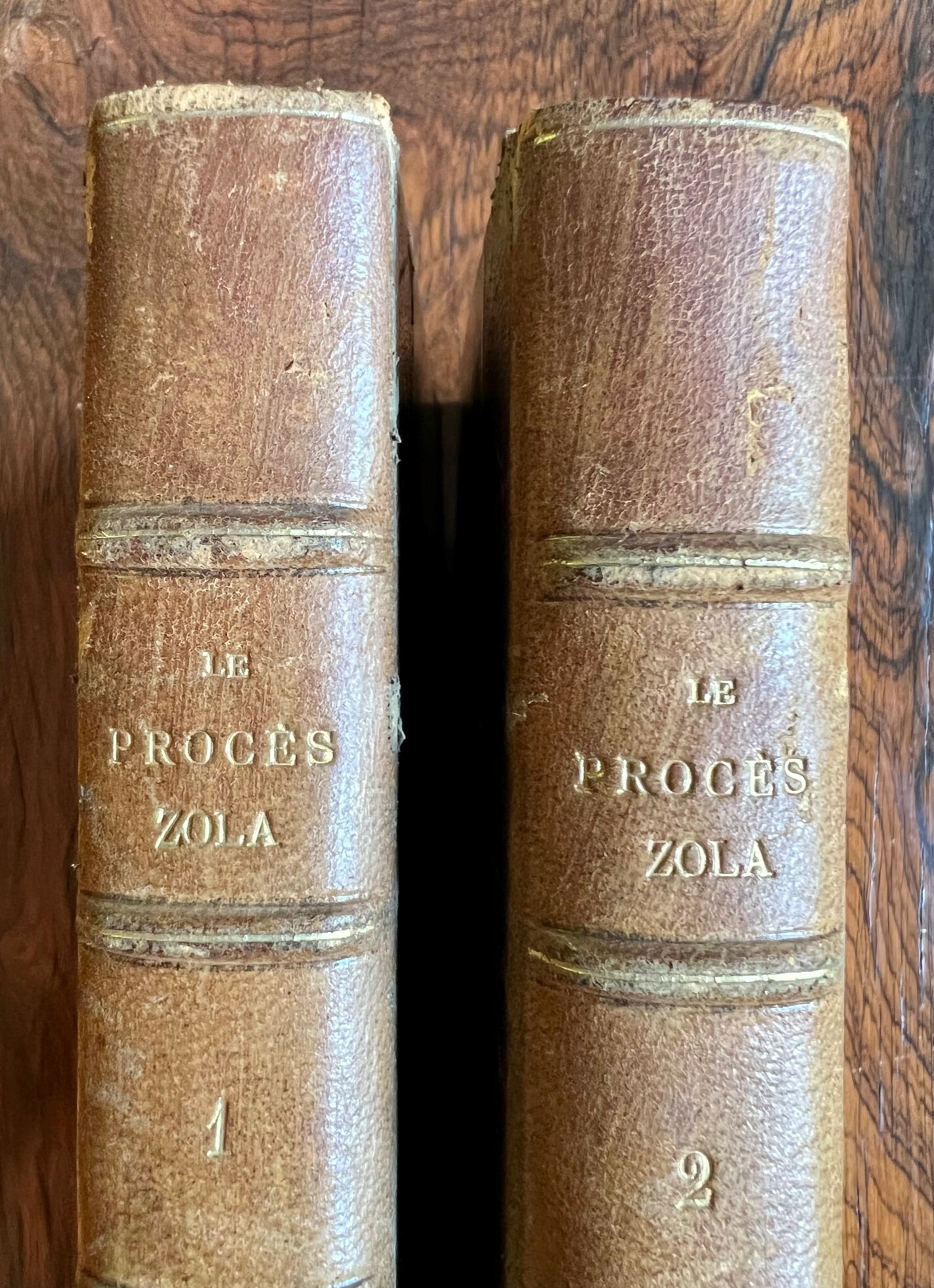

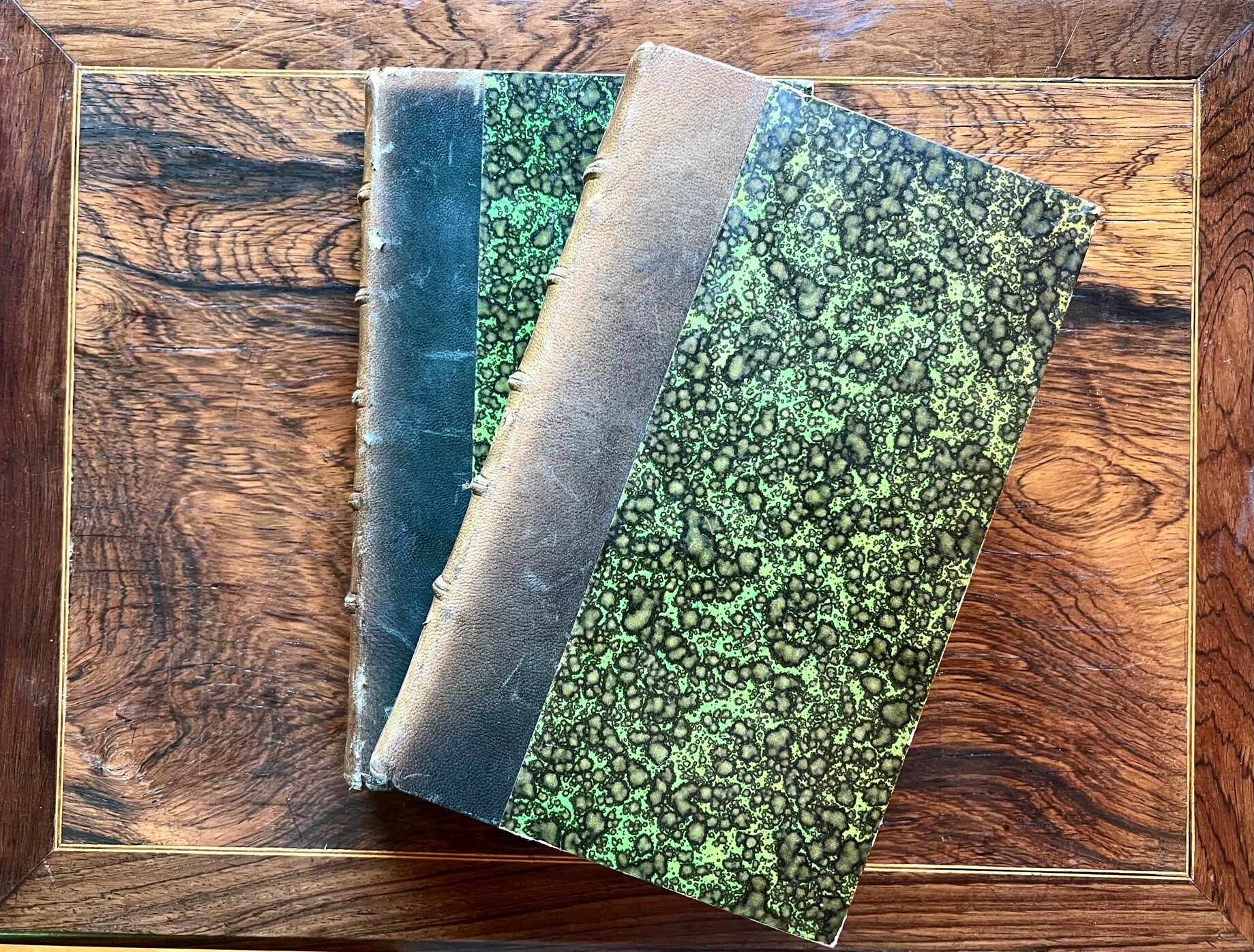

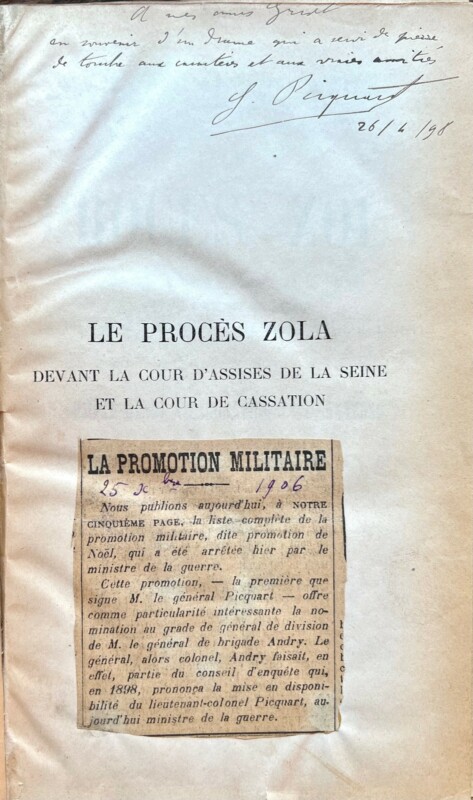

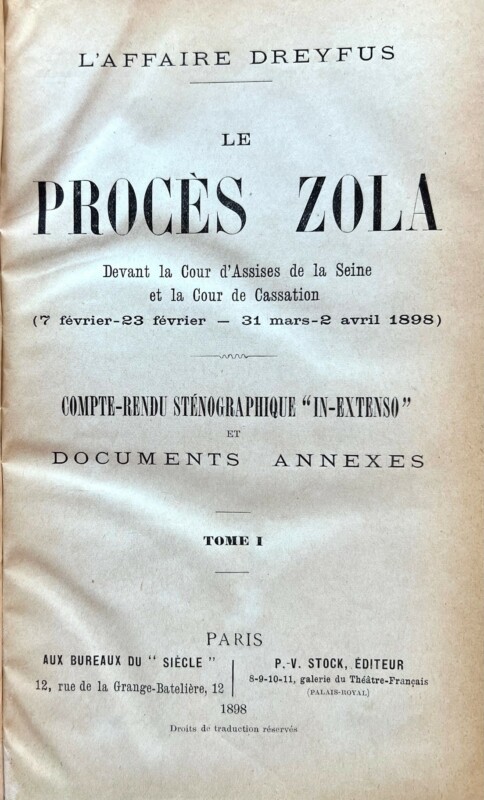

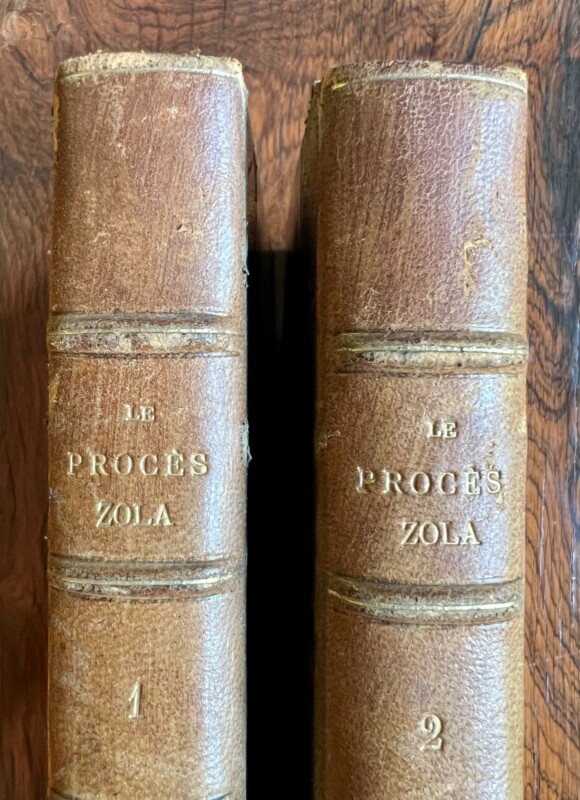

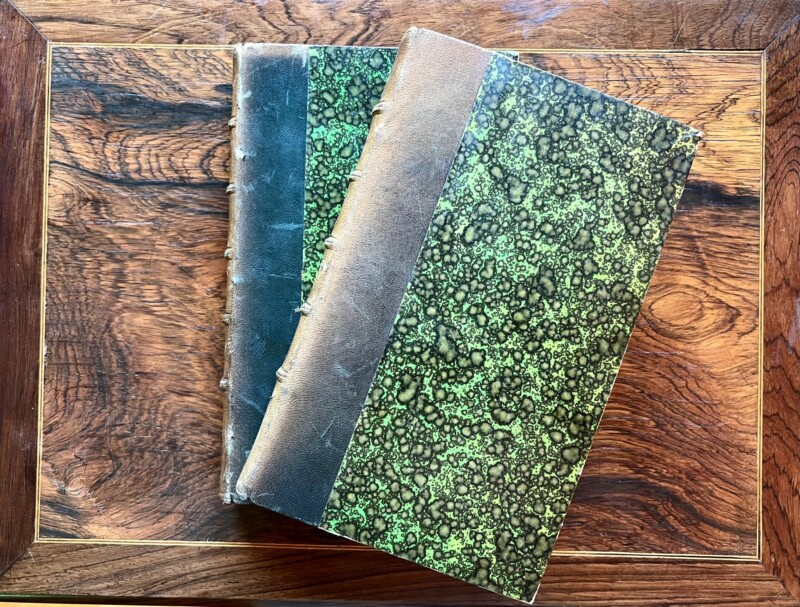

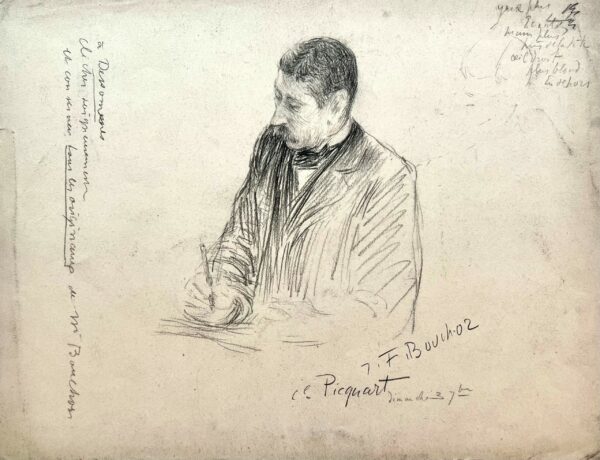

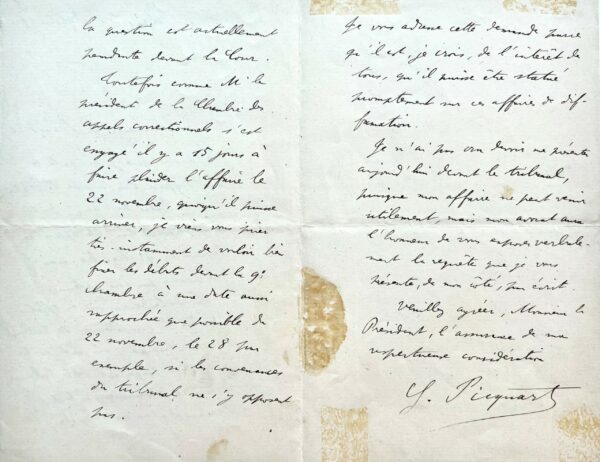

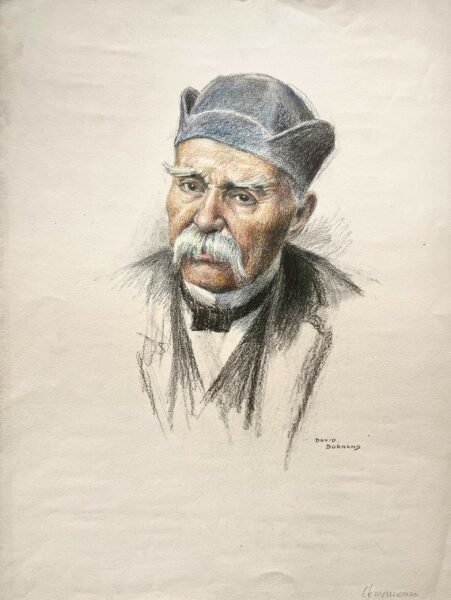

PICQUART, GEORGES-MARIE. (1854-1914). French army Lieutenant-Colonel, Dreyfus’ instructor at the War College, and chief of military intelligence who, in 1896, after reviewing a pneumatic tube telegram (the petit bleu) sent to Esterhazy from the German Embassy’s military attaché, Schwartzkoppen, opened an investigation into Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy, the agent whose espionage activities had been pinned on Dreyfus. Signed book. Le procès Zola devant la cour d’assises de la Seine et la cour de Cassation (Paris: Stock; April 1898; first editions). 548 pp. and 538 pp. 8vo. N.p., April 26, 1898. The official transcript of Emile Zola’s (1840-1902) trial, including facsimiles of relevant documents bound into the second volume. Inscribed by Picquart on the half title of volume one, less than three weeks after the trial’s conclusion on April 2, 1898: “À mes amis Griset [?], En souvenir d’un drame qui a servi de pierre de touche aux caractères et aux vraies amities, G. Picquart 26/4/98” (“To my friends Griset [?], In memory of a drama that served as a touchstone for character and true friendships, G. Picquart 4/26/98”). Additionally signed on the second free-front endpaper by the Dreyfusard journalist, publisher and future French Prime Minister GEORGES CLEMENCEAU (1841-1929; “G. Clemenceau,”), responsible not only for publishing J’Accuse…! but more than 650 additional articles defending Dreyfus.

Appearing in the newspaper L’Aurore on January 13, 1898, Zola wrote J’Accuse…! to trigger his arrest for libel in the hope that those who had conspired to convict Dreyfus would attack him and, in so doing, re-focus attention on a case that the public had by and large forgotten since the captain’s deportation to prison on Devil’s Island in 1895. On the same day, just two days after Esterhazy’s acquittal (which had precipitated Zola’s article), Picquart was arrested for revealing military secrets to the public and imprisoned. Zola’s prosecution became a public sensation when his trial commenced on February 7, 1898. Found guilty on the 23rd after the jury deliberated for just 40 minutes, Zola was sentenced to one year in prison and a fine of 3,000 francs. On April 2nd, his conviction was overturned on a technicality, likely the reason for Picquart’s somewhat optimistic inscription. However, Zola was found guilty a second time on July 18, 1898, whereupon he fled to England and lived in exile for nearly a year. Following his return to France, Zola published a collection of essays about the Dreyfus Affair, entitled La Vérité en Marche, in 1901. Though his enemies accused him of profiting by his involvement in the Dreyfus Affair, his association with the case was not only detrimental to his career but almost certainly led to his death under mysterious circumstances in 1902, when he fell victim to asphyxiation due to a backed-up chimney in his home. Regrettably, Zola did not live to see Dreyfus’ guilty verdict reversed on July 12, 1906 – a triumph not only for Dreyfus and his supporters, but a posthumous one for Zola as well.